Trending Among Voters: Education

As a research and advocacy organization, SCORE frequently checks the pulse of voters regarding various education issues. From public opinion surveys to focus groups, understanding what is on the minds of Tennesseans is important as we work to improve education for all students in our state. You can reference a few of our previous public opinion surveys here.

SCORE’s most recent public opinion survey was conducted March 29-April 1 by our partner, Public Opinion Strategies. We surveyed 500 registered Tennessee voters from across the state and asked them about the most important and talked about education issues in 2019.

The survey found that education continues to be a top issue among voters in Tennessee. When asked about what is the top issue facing Tennessee, education was second in the minds of voters. Tennesseans placing a high priority on education policy is understandable given the tremendous progress our state has made over the past ten years, including the designation as fastest-improving state in student achievement from 2011-2015.

The state-level policies that enabled that success also have high levels of support among voters.

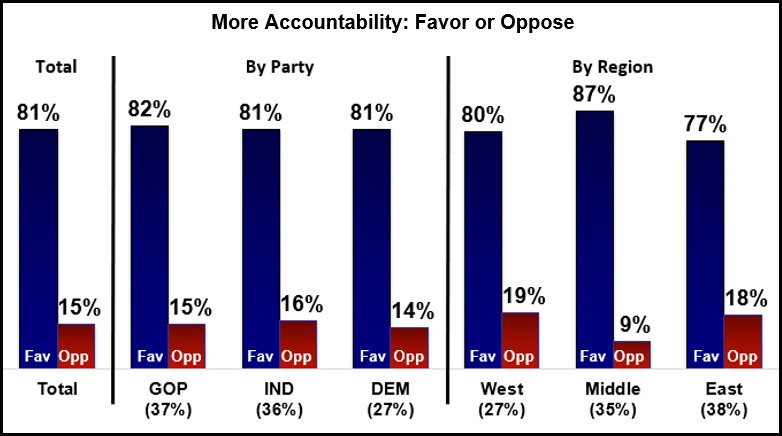

Accountability has been at the center of the education policy conversation for the past several years. In this poll, voters were asked about policies related to accountability as a whole. When asked whether or not voters favored more accountability in schools, including assigning letter grades to schools, state intervention, teacher evaluation, and transparency, voters overwhelming said they wanted more accountability-related policies: 81 percent favoring more and 15 percent opposing more. This support cut across political parties and geographic regions of the state.

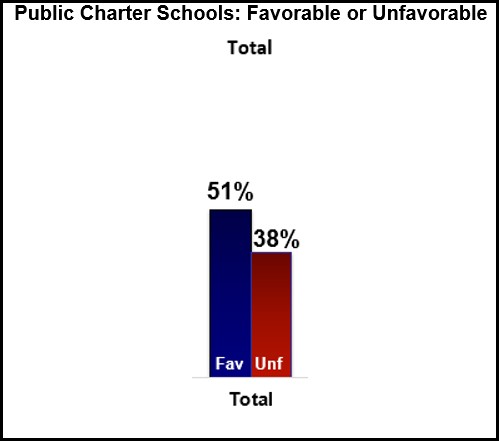

School choice is one of the most-discussed policy areas of 2019, and voters are clearly paying attention. After defining a public charter school as “public schools operated by independent, nonprofit governing bodies that receive state and local funding similar to other public schools,” the survey asked whether voters have a favorable or unfavorable view of public charter schools. Voters have an overall favorable impression: 51% of voters having a favorable view of public charter schools and 35% having an unfavorable view.

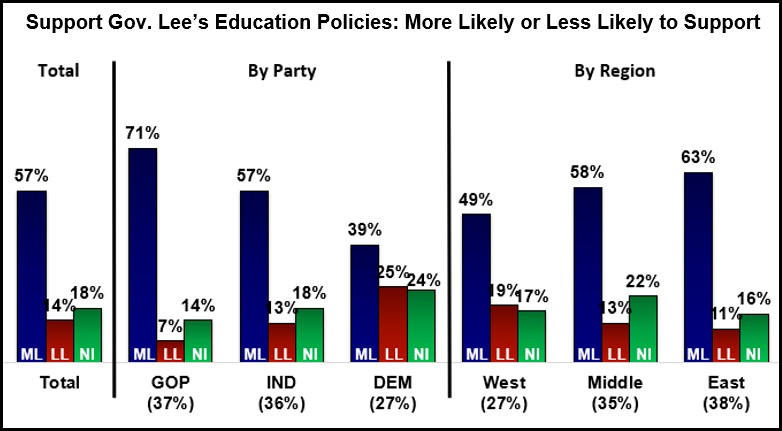

With new leadership in Tennessee following the 2018 election cycle, voters’ impressions are always an interesting data point. Governor Lee began his term with a focus on education, and his first major policy proposal was the Governor’s Investment in Vocational Education (GIVE) act, followed by the Future Workforce Initiative. When voters were asked if their state legislator supported Gov. Lee’s education policies would it make them more or less likely to support them, the results were overwhelming: 57% said it would make them more likely, 14% said less likely, and 18% said no impact.

These are just a few of the most interesting questions from SCORE’s most recent public opinion survey. You can see additional results here.

[Read More at SCORE] Read MoreHow do states’ ESSA plans rate in promoting equity?

Months after the approval process for all states’ consolidated Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) accountability plans wrapped up in September 2018, each state has identified its own set of indicators and has been working to implement the federal law. However, as this shift takes place, there’s still an underlying question: How well do these plans aim to support struggling schools and ensure equity?

On Wednesday, the National Urban League (NUL) released its ESSA equity review grading the plans of 36 states and the District of Columbia along 12 indicators. Using metrics including resource equity, educator equity, and supports and interventions for struggling schools, the organization assigned a rating of “excellent,” “sufficient” or “poor,” with these evaluations serving as a “preliminary indicator” of how states plan to implement the policy, the report says.

“The genesis of this report was really to elevate equity in this conversation knowing that these plans represent a blueprint for action,” Susie Feliz, the vice president for policy and legislative affairs in the NUL Washington Bureau, told Education Dive. “They represent promises that state leaders intend to make to ensure that every student does, in fact, succeed.”

The grades

Since the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act in 2015, states have been charged with revamping each of their strategic plans to evaluate student performance. Instead of one-size-fits-all standardized tests and uniform accountability measures, the move from No Child Left Behind to ESSA made room for more flexibility for states and a heavier emphasis on individual student progress.

ESSA also aimed to tackle the achievement gap and address inequities that exist between and within states. Since its implementation, some states have made efforts to increase equity through initiatives including implicit bias training, issuing annual equity reports and hiring “equity specialists” to work with teachers.

In assessing these efforts, the NUL’s report card deemed nine states “excellent” in incorporating equity, while 20 were graded “sufficient” and eight were rated “poor.”

Colorado, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma and Rhode Island got “excellent” ratings, meaning their ESSA plans “were off to a strong start making the most of opportunities to further advance equity, with some areas for improvement,” the report says.

The bulk of states surveyed in the report — 20 in total — got a “sufficient” grade, which the NUL report defines as plans being “adequately attentive to opportunities to further advance equity, with several missed opportunities, and a few areas deserving urgent attention.” Among these states is Washington, Texas, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, North Carolina and Maryland. The District of Columbia also falls in the “sufficient” category.

Roughly 22% of the states, or eight in total, evaluated in the NUL report were deemed “poor” — that is, their plans “missed opportunities to further advance equity in a majority of areas with several areas needing urgent attention.” Several high-population states — including California, Florida, Georgia, Virginia and Arizona — landed in this category, along with Kansas, Missouri and Michigan.

The indicators

In assigning grades, the NUL used 12 metrics that span a wide variety of issues in educational equity, including breaking the school-to-prison pipeline, resource equity, educator equity, and supports and interventions for struggling schools. Each state, plus D.C., was rated “excellent,” “sufficient” or “poor” in each of these indicators, which helped calculate its overall score.

In many cases, regardless of what overall grade a state earned, there were clear trends in performance in each area. NUL rated the majority of states as excellent in the goals and indicators category — defined by the organization as “having ambitious academic goals for all students and for each student subgroup” — as well as stakeholder engagement, equitable access to early-childhood learning, equitable access to high-quality curricula, and equitable implementation of college and career standards.

Additionally, in two-thirds of the categories, such as resource equity, educator equity, breaking the school-to-prison pipeline and out-of-school time learning, states were most often graded as “sufficient.” The top three “poor” categories were supports and interventions for struggling schools, resource equity and subgroup performance, which measures how much state ESSA plans include all student subgroups across all grades.

Feliz said her organization is “optimistic” about the results.”We are optimistic in the sense that there is certainly an opportunity for growth and improvement for every state, and in particular, the states that were rated ‘poor,'” she said. “We certainly hope that they revisit their plans with a new look, and that they engage their stakeholders in a collaborative process to work together to identify a better road to achieving equity in those states.”

Moving forward

As part of its recommendations, the NUL urged Congress to revisit state plans and hold hearings on the issues highlighted as a means of paving the way for improvement. It also suggests that at a state level, leaders take notes from their peers, and from a budgetary standpoint, reevaluate spending to ensure it is distributed equitably – which a report issued in April says is not taking place.

Another key takeaway, Feliz said, is for communities to discuss and advocate for their states to make any needed changes to strengthen their school systems.

“ESSA represents a historic opportunity to meaningfully engage local communities, families and parents that are directly impacted by the law, but also by states’ interpretations of the law and the policies and practices they put in place,” Feliz said. “There’s a real opportunity for administrators and principals to have meaningful conversations and involve community stakeholders … and solicit their input on these ESSA plans.”

[Read more at Education Dive] Read MoreInvesting in Principal Talent Pays Off in Higher Math and Reading Scores, Study Finds

Principals who’ve had attention at every point in their development as a school leader—including selection, preparation, hiring, placement, and coaching after they are on the job—were linked to stronger reading and math achievement and to longer tenures in their jobs at the helm of schools.

Those clear findings—from a new study of six school districts that made heavy investments in strengthening their cadre of school leaders—underscore the key role principals play in their schools’ academic success. The report, by researchers at RAND Corporation, looked at the six-year, $85 million “principal pipeline” initiative supported by the Wallace Foundation. (Coverage of education leadership in Education Week is supported in part by the Wallace Foundation.)

Schools that got new principals in 2012-13 or later as part of the pipeline initiative outperformed other schools in their states that were not in the program by 6.22 percentile points in reading and 2.87 percentile points in math three years after the new school leader was hired, researchers found.

RAND also found that new principals in the pipeline districts were 5.8 percentage points more likely to stay in their schools for two years than new principals in non-participating districts, though there was variation among districts.

Perhaps most significantly, the report found statistically significant academic growth in the schools that were among the lowest-performing in the pipeline districts that had gotten new principals. And while new principals who were products of the initiative posted the most growth, other school leaders in the pipeline districts also saw gains.

That specific finding exceeded the Wallace Foundation’s original hypothesis on how effective principals could boost achievement when it launched its initiative to work with districts to thoughtfully prepare, select, place, and support principals.

“What these results say is that principal pipelines are a strategic and systemic approach to create districtwide student achievement” growth, said Jody Spiro, the director of the foundation’s education leadership program.

“All principals in the district benefitted…,” she said. “They benefitted from having clear leader standards. They benefitted from these more rigorous hiring procedures, from being better matched to their schools, from having evaluation systems that the research tells us the principals perceived as fair and useful. It became bigger than…a ‘training program’ for principals. It became a whole system approach.”

‘Bang for the Buck’

The districts in the program were Charlotte-Mecklenburg, N.C.; Denver; Gwinnett County, Ga.; Hillsborough County, Fla.; New York City; and Prince George’s County, Md.

Their results mirror what’s happened in Chicago, where school leadership has been an improvement strategy for 20 years, said Heather Y. Anichini, the chief executive officer of The Chicago Public Education Fund.

One of the validating findings in the RAND analysis was the academic gains among the lowest-performing schools—those most in need of effective principals, Anichini said.

“That’s something we’ve been seeing here for a while, too, but it isn’t necessarily something that’s focused on a lot in the literature,” she said.

“If it is the kind of strategy that can really make a difference, not just generally, but specifically in places where students are struggling, then it’s something we must pay more attention to.”

That finding may seem to fly in the face of research and conventional wisdom suggesting that newly minted principals shouldn’t lead struggling schools, said Doug Anthony, an associate superintendent in Prince George’s County.

But in the pipeline districts, new principals went through rigorous selection, got relevant training, and were matched based on their strengths and the school and community’s needs, and they were provided with mentor and other support systems, said Anthony.

“I think this actually dispels that to some extent, and that if you actually equip people and build leaders who have already come with a certain skill set and sharpen that skill set and are particular about how they are developed and identified and supported, you can actually see bang for the buck in student achievement even in your toughest schools,” Anthony said.

Prince George’s County made dramatic changes to its school leadership program. It revised its standards for leaders which guide how it evaluates and supports aspiring and sitting principals. It created data systems to track principals’ performance and expanded partnerships with university-prep programs.

The RAND researchers said they know of no other districtwide improvement strategy that yielded such significant academic results on such a large scale.

Collectively, the districts in the pipeline initiative serve nearly 1.7 million students.

The effects of the pipeline were evident early, another key finding, Spiro and others said.

And districts can start reaping the gains right away.

While setting up a preparation program takes time, districts can get early wins by sharpening leader standards, matching principals’ skill sets with the needs of schools, and retooling the work of administrators who manage principals.

“Every district has something of a pipeline because they all hire principals, but it’s a matter of if it’s systemic,” Spiro said.

The program was also relatively affordable for districts, the report found. Over five years, the initiative cost $210 per student if looking at its impact districtwide and $373 if looking solely at students in schools with principals who received the full “treatment” of the initiative.

RAND’s research did show varied results. Math scores in one unnamed district, for example, were negative and researchers found positive but not statistically significant effects in math achievement in two others. There was also variation in the study’s findings on principal retention.

Return on Investment

Glenn Pethel, an assistant superintendent in the Gwinnett County schools, said that districts and state education agencies should pay attention to the report.

“It should cause districts to stop and reflect and think about where they are making investments,” Pethel said. “I hope that it would cause them to see that investing in a principal pipeline does have a significant return on investment.”

That’s not always an easy pivot for districts, which tend to focus, understandably, on teachers. District leaders also gravitate to programs that can yield quick results. And building pipelines relies on relationships, which pose a challenge in a sector susceptible to frequent turnover.

Cultivating leadership has always been a district priority in Gwinnett County, Pethel said. The district’s superintendent, J. Alvin Wilbanks, has been in his position for more than two decades, and the district is always looking to spot and shape new talent.

When Pam Williams moved from Palm Beach County, Fla., to Gwinnett County in 2006, she was not looking to become a principal.

But her principal quickly spotted her talent in the classroom and her knack for team-building. He brought her onto his leadership team and steadily supplied her with books on instruction and leadership.

He urged her to apply for the district’s aspiring principals program.

Williams is now principal of Bethesda Elementary School, which was among the bottom 20 percent of the district’s schools when she took over in 2013.

In the last two years, it’s consistently landed in the top 20 percent of the district’s schools and among the top Title 1 schools in Georgia.

Williams credits the district’s two preparation programs in which she participated—which were developed during the pipeline initiative and featured experts from the district’s curriculum staff, sitting principals, and other building leaders, and the superintendent as lecturers.

Her mentor during her first two years on the job was “priceless,” she said.

While she had her own ideas on how to turn around the school, its success is mainly due to the preparation program and district support, she said.

“Anything that I’ve implemented was definitely not straight from my brain, that’s for sure, she said. “It was definitely ideas that I learned from the program.”

[Read more at Ed Week] Read MoreCan scholarship dollars help solve the college ‘undermatching’ problem? This charter network wants to find out

Amy Christie has seen it many times. A student gets into a great college and heads to admitted students’ weekend, excited to explore their academic future.

Then they start examining financial aid packages — and the numbers just don’t add up.

“Realizing you can’t make that choice is really hard,” says Christie, the senior director of college access and success at the Achievement First charter network. “You’ve earned your spot and you just can’t go.”

The result: Instead of enrolling at that school, the student ends up somewhere less expensive and less selective. Researchers call the phenomenon of enrolling in a college that doesn’t line up with academic skills “undermatching,” and it’s more common among students from low-income families.

Achievement First, which operates 36 schools across three states, is about to try a new way of addressing the problem. The network’s Brooklyn board approved a plan last week to offer scholarships to students who opt to attend a more expensive school with a higher graduation rate for black and Hispanic students.

“We believe that fairly modest amounts of scholarship money (~$3,000-$7,500/year) could have a significant impact on the matriculation decisions that a subset of our scholars and families make,” the proposal says.

It’s the latest attempt by a charter network serving mostly students of color from low-income families to help their graduates make it all the way through college — something that the schools acknowledge is a challenge. One reason is the financial burden college can put on students and their families.

“What our counselors are saying is that sometimes it really is just a modest amount of money,” Achievement First CEO Dacia Toll told board members.

Here’s how the scholarship will work: To be eligible, a high school senior must be choosing among colleges, including one that is more expensive but has a substantially higher graduation rate among black and Hispanic students. Students would be selected based on their financial need, academic track record, and other qualities like motivation.

Roughly 20 students who graduate this year from one of its Brooklyn high schools would be eligible for an average scholarship of $5,000 each year of college. The charter’s board approved allocating $100,000 annually for the program, money that will come from general funds the network receives from the state of New York. If the program proves successful, Achievement First hopes to expand it, perhaps by raising philanthropic funds.

“I think it’s really interesting,” said Matt Chingos, the vice president of education data and policy at the Urban Institute who has studied undermatching. He said he hadn’t seen scholarship programs as specifically targeted as Achievement First’s.

“For an individual student, there’s nothing inherently wrong with going to a less selective college,” he said. “The reason folks are concerned about it — and the reason I think it’s a problem — is because it’s a pattern in the data we predominantly see from lower-income families.”

“That matters, because more selective colleges aren’t just fancier and give you a better sticker on your car. They come with more resources and have better graduation rates.”

There is evidence in a number of states — Michigan, Florida, and Wisconsin — that need-based scholarships increase the chances that low-income students will enter college and earn a degree.

There’s also research, consistent with Achievement First’s approach, suggesting students benefit from attending a more selective, better resourced school. “People are more likely to graduate from places where more people graduate,” Chingos said.

Two studies in New Mexico and Tennessee do offer a note of caution, though, suggesting that scholarships may not end up helping lower-achieving students complete college. But even in these studies, relatively high-achieving students do benefit.

This scholarship won’t directly help college students with unexpected costs or living expenses. A 2016 KIPP survey of its alumni found that 43 percent reported missing meals while in college for financial reasons. Achievement First also maintains an emergency fund of $67,000, according to a spokesperson, which between 12 and 24 alumni tap into annually. KIPP recently expanded a similar program it started in Washington D.C. in 2014, with four of its regions starting their own funds with about $40,000.

Christie hopes the extra funding could help reduce the anxiety of students who do opt for schools that might put financial strain on their families.

“When there has been a student who actually has chosen the more expensive institution for all the right reasons, and the family hunkers down and says, ‘OK, we’re really going to make this work,’ but it’s at a level of stress — there’s this sentiment of living semester by semester or just being kind of on edge a little bit because you know that bill is coming,” she said.

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read MorePellissippi State, Cumberland University saw higher enrollment, degree completion with Tennessee Promise

Pellissippi State Community College and Cumberland University saw higher enrollment and degree completion since Tennessee Promise was launched four years ago, according to a new study.

Tennessee Promise is a last-dollar scholarship and mentoring program that gives high school graduates five consecutive semesters of free tuition at an eligible Tennessee community or technical college. The program was launched in fall 2015.

The reports, done by the University of Tennessee-Knoxville’s Postsecondary Education Research Center, are the first two in a series of reports that are looking at the impact of Tennessee Promise at specific higher education institutions in Tennessee.

Interim President Randy Boyd, who previously served as Gov. Bill Haslam’s adviser for higher education and helped create the Tennessee Promise program, said the program has helped to change how Tennesseans think about education.

“Because of Tennessee Promise, because of UT Promise, those programs, we’re beginning to change the culture,” Boyd said. “We’re beginning to have a state where students can be born in a family in a state where they can believe in the future because they’re going to have the opportunity to go on and get a higher education and have a more successful life.”

Pellissippi State saw increased minority enrollment

Pellissippi State Community College, the largest community college in Tennessee, had a 25% increase in first-time, full-time freshman enrollment during the first semester of Tennessee Promise. Additionally, first-time, full-time freshman enrollment had increased by 40% by the fall 2018 semester.

“The study shows that Tennessee Promise both increases accessibility to college and provides incentive for more students to stay the course. At Pellissippi State we are happy to play a role in helping a larger group of Tennesseans earn a post-secondary credential,” said PSCC interim Vice President of Academic Affairs Kathryn Byrd.

Since Tennessee Promise launched, Pellissippi State also saw an increase in the number of African American and Hispanic students enrolled.

Pellissippi State Community College, the largest community college in Tennessee, had a 25% increase in first-time, full-time freshman enrollment during the first semester of Tennessee Promise. (Photo: Michael Patrick/News Sentinel)

The number of African American students grew from 5% in the fall 2015 freshman cohort to 6.4% in fall 2018. Hispanic student enrollment grew from 4.4% in the fall 2015 freshman cohort to 5.9% in fall 2018.

In total, Pellissippi State had 10,894 students enrolled for the fall 2018 semester.

Cumberland University

At Cumberland University, a private university in Lebanon, Tennessee, the number of students enrolled in Tennessee Promise grew from 68 in 2015, when the program started, to 414 in the fall of 2018. Cumberland University has 2,405 students enrolled, according to the school’s website.

“Among the first cohort of Tennessee Promise students at Cumberland University, 44.9 percent completed their associate’s degree in the first five semesters, compared to 23.6 percent across the state,” according to a news release from UT.

Cumberland University President Paul Stumb said the school’s focus on retention has helped drive students to complete their degrees, including a free tutoring program and student retention center.

“Our faculty and staff are devoted to keeping these students in school and getting them to the goal,” Stumb said.

Cumberland University also retained a higher percentage of Tennessee Promise students each semester than statewide averages.

Jackson Decote chose Cumberland University in Lebanon because it is one of the few four-year institutions that accepts Tennessee Promise students. (Photo: Larry McCormack / The Tennessean)

Like at Pellissippi State Community College, the number of minority students at Cumberland University also increased under Tennessee Promise.

Enrollment of Hispanic students grew from 1.5% to 5.6%, African American students grew from 4.4% to 5.1%, and Native American and Asian student enrollment grew from less than 1% each to 1.7% and 1.2%, respectively.

In total, over 1,000 Tennessee Promise students have attended Cumberland University. Stumb said the Tennessee Promise students “are bringing a lot of life to our campus.”

“Our mission is to change the lives and transform lives of young students, and this has allowed us to do that for students who otherwise might not have the opportunity to go to college,” Stumb said. “They certainly would not have had the opportunity to go to a four-year college like Cumberland without the Tennessee Promise.”

Tennessee Promise students take more credit hours

The study also found that students enrolled in Tennessee Promise take more credit hours in their first semester and are more likely to complete their degree or certificate than students not enrolled in the program.

In the first group of first-time, full-time students, 23% completed their program in five semesters. Of students not enrolled in Tennessee Promise, 7.6% completed their program in the same time period.

Interim UT System President Randy Boyd speaks at a news conference about Tennessee Promise on April 2, 2019. (Photo: Monica Kast/News Sentinel)

Students in the first Tennessee Promise cohort had a three-year completion rate of 30.1%, whereas the year before the program started, the three-year completion rate was 23.5%.

UT Promise to launch fall 2020

Last month, UT announced it will launch a last-dollar scholarship program similar to Tennessee Promise that will allow students to attend a UT school free of tuition and fees.

University of Tennessee Promise: What students need to know to get free college

The program, called UT Promise, will launch in fall 2020 and will cover tuition and fees for Tennessee high school graduates with a household income of less than $50,000 a year and who are recipients of the state’s HOPE scholarship.

UT Promise will be available for undergraduate programs at the UT Knoxville, Chattanooga or Martin campuses.

[Read more at Knox News] Read MoreCollege-ready students? How about student-ready colleges? | Opinion

America’s community colleges serve as entry points to opportunity for millions of students.

Regardless of an applicant’s background or circumstance, these institutions provide programs of study that prepare students with valuable credentials to secure living-wage jobs or with the credits necessary to pursue further study at bachelor’s degree-granting institutions.

As president of Nashville State Community College, I am committed to the vital role community colleges play in Tennessee’s higher education system. I believe we exist to serve not just the current but the emerging needs of our workforce. Through the Tennessee Promise and Tennessee Reconnect programs, the state has recognized that community and technical colleges are critical pathways toward increasing the number of Tennesseans with a credential beyond a high school diploma.

However, increasing access to postsecondary education is not enough. Completion is the goal. Yet far too many of our students arrive on campus only to find their institutions are unprepared to support their success.

Nashville State serves a challenging population. Census data show 29 percent of Nashville’s children live in poverty. Metro Nashville Public Schools have a high school graduation rate of 80 percent, yet only 61 percent of those graduates go directly to college. According to the ACT college entrance exam, only 24 percent are ready for college-level work.

Although Nashville’s college attainment rate has increased in recent years, rising to 47.6 percent in 2017, the percentage of good-paying jobs that will require at least a technical certificate or associate’s degree is also growing – and at a quicker pace than our attainment rate. It is concerning to know that a significant number of people who live in Nashville will not have the education and training necessary to fill many of the new jobs being added to our economy.

At Nashville State, a significant number of our first-time enrolled students drop out before returning for their second year. We know we can and must do better for the sake of our students, our community and our economy. One thing I know is we cannot do this alone.

We are thankful for the support of many partners such as Complete Tennessee and others who are helping the college identify why students drop out of college. One significant outcome of this work is Mayor David Briley’s proposed Nashville GRAD program. Nashville GRAD will not only provide the financial support beyond Tennessee Promise and Tennessee Reconnect to cover expenses such as textbooks, transportation and certification exams for Nashville State and the college of applied technology in Nashville, but equally as important, is providing the resources for the college to pilot a new holistic approach to student support.

At the very heart of it all is my desire to change the narrative around students being “college-ready” to one where our colleges are ready to serve the students we receive. My dream is to find the resources that equip us to design a holistic support system to meet the individual needs of all students. As the data continue to show our students have a diverse range of challenges and many do not have the resources or support to complete college.

In Complete Tennessee’s latest State of Higher Education report, the nonprofit rightly calls for a deeper commitment to addressing the state’s persistent equity gaps. According to the report, “Without an aggressive, comprehensive approach to increase graduation rates for all students while simultaneously narrowing graduation rate disparities for historically underserved populations, higher education attainment rates will continue to have a strong relationship to income and race and run the risk of perpetuating cycles of poverty.” This kind of approach involves financial support, but it also requires institutions provide the highest level of service to each student, ranging from course advising and mentoring to creating welcoming campus cultures where every student knows they belong.

By being more student-ready, our colleges can better meet the mission to empower people for careers and community involvement that makes life better for everyone.

Dr. Shanna Jackson is the fifth president of Nashville State Community College. She previously served in leadership roles at Columbia State Community College and Volunteer State Community College.

[Read more at the Tennessean] Read MoreAldeman: Why Aren’t College Grads Becoming Teachers? The Answer Seems to Be Economic — and the Labor Market May Be Starting to Improve

Updated April 2

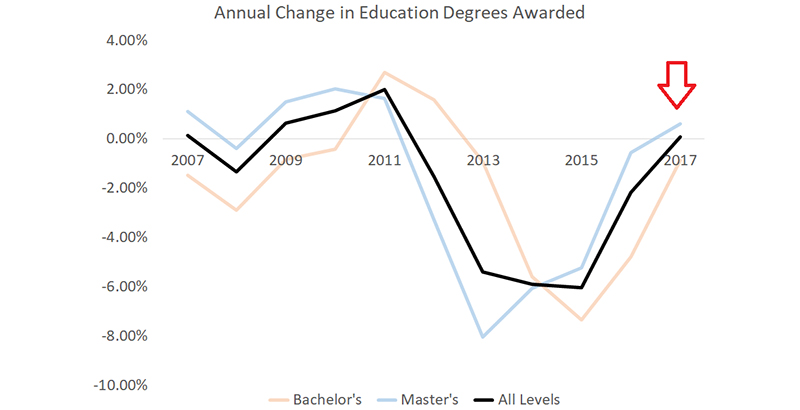

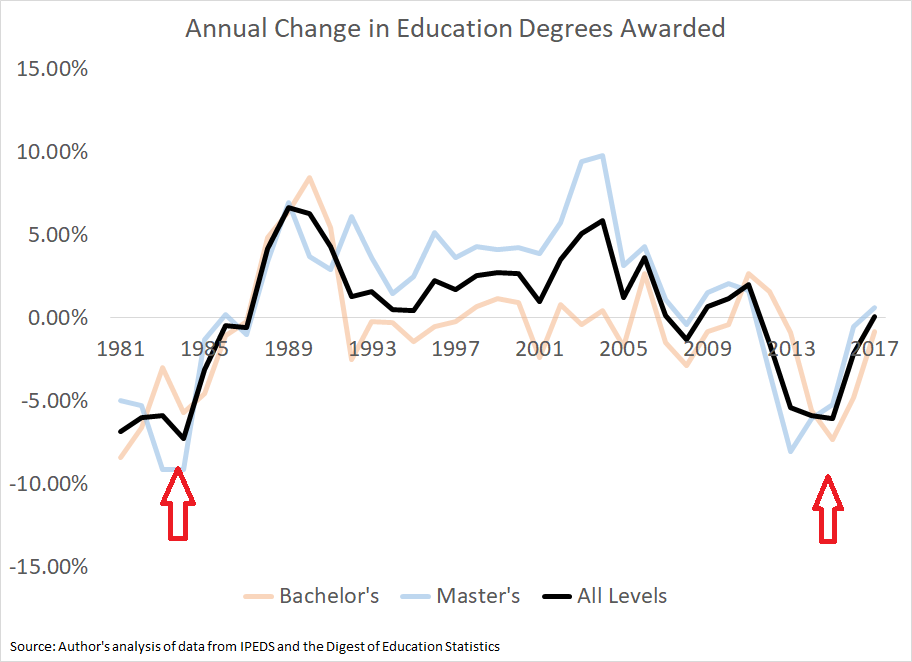

For several years, the education world has been worried about the decline in the number of students interested in becoming a teacher. In the wake of the Great Recession, the number of students pursuing education degrees and earning their teaching licenses began to plummet, and the declines were particularly severe in certain states.

But was this crisis mainly due to policy decisions in the education sector, or more a function of underlying economic conditions? I’ve long been on team economics. In support, I’ve pointed to a 2015 study showing that college students made their decisions about what major to pursue based on prevailing economic conditions. In fact, that study found that the number of students pursuing education degrees was more susceptible to labor market trends than any other field of study. When recessions have hit the American economy over the past 50 years, both men and women were less likely to want to become teachers and instead turned to fields like accounting and engineering.

The economy has improved markedly over the past few years, so according to the economic explanation, we should start to see more young people pursuing a teaching career. Is that happening?

My tentative answer is yes. We’re starting to see preliminary signs that the supply of new teachers is beginning to grow again. According to a reportissued in April, California has seen four consecutive years of increases for initial teaching credentials. And, while it made national headlines when Teach for America, the country’s largest provider of new educators, saw its applicant pool fall significantly from 2013-16, its subsequent rebound has happened much more quietly.

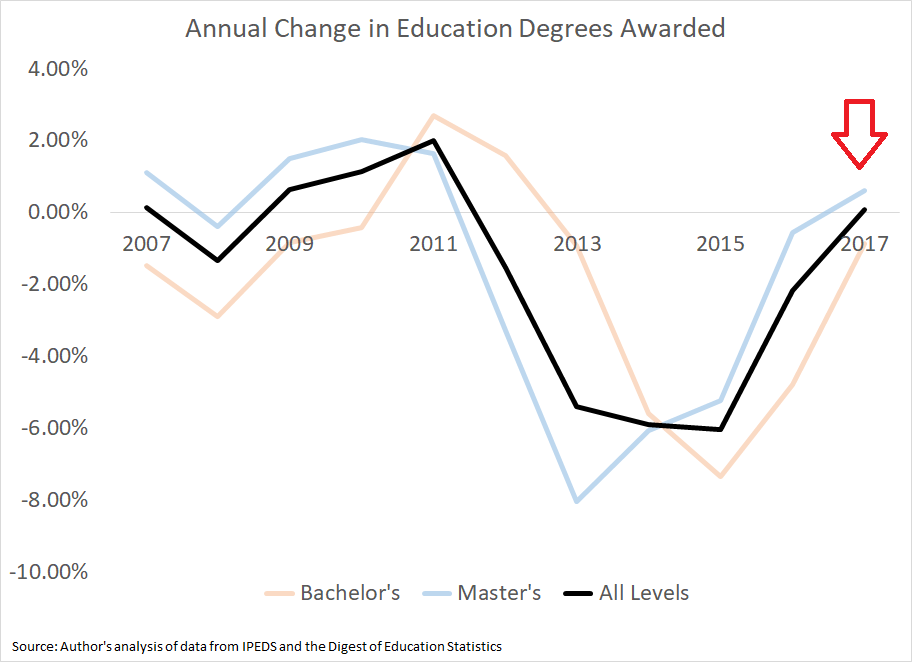

National data are starting to confirm these anecdotes. The most recent national statistics we have on new teacher licensures come from 2015-16, but we now have provisional data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System on college completions for the 2016-17 school year. Those numbers show a promising trend. After bottoming out in 2013, the year-over-year changes in the number of students completing an education degree got smaller and smaller. And in 2017, the most recent year for which we have data, we had the first year-over-year increase in college graduates with education degrees since 2012. It’s still not much — 2017 was just .62 percent higher than 2016 — but it could be the start of a promising trend.

It has been a while, but this story has played out in American schools before. In the early 1980s, the number of young people graduating with education degrees was declining by 5 to 9 percent year-over-year. But things started to look less bad by 1986, and then we had 20 straight years of gains from 1988 through 2007.

These trends also match up with survey results about whether parents would want their children to become teachers. Just like the number of education degrees, answers to that question bottomed out in the early 1980s, rebounded in the late 1980s and remained high throughout most of the 1990s and early 2000s. Although those survey results hit a new low last year, the increase in the number of college students pursuing education degrees may portend another rise in the perceptions of parents.

Now, I’m not saying we’re likely to see the same stretch of gains in terms of perceptions or results we saw in the 1990s and early 2000s. That would depend on lots of other factors, including the number of college-age students and future economic conditions.

Nor am I saying the teacher labor market is perfectly balanced today. Even if the supply of new teacher candidates is starting to improve, it still may not match the growing demand for new educators. And as Kaitlin Pennington McVey and Justin Trinidad noted in a report for Bellwether Education Partners in January, some subject areas are chronically short of high-quality teacher candidates regardless of the underlying market conditions.

But these green shoots are an early indication that the teacher labor market may be starting to thaw. We’ll have to wait for more data to confirm these preliminary findings, but there’s reason to be hopeful that we’re on a positive trajectory.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreNew Numbers Show Low-Income Students at Most of America’s Largest Charter School Networks Graduating College at Two to Four Times the National Average

A fresh look at the college success records at the major charter networks serving low-income students shows alumni earning bachelor’s degrees at rates up to four times as high as the 11 percent rate expected for that student population.

The ability of the high-performing networks to make good on the promise their founders made to struggling parents years ago — Send us your kids and we will get them to and through college — was something I first reported on two years ago in The Alumni.

Writing the new book I’m about to publish with The 74, The B.A. Breakthrough: How Ending the Diploma Disparity Can Change the Face of America, provided the chance to go back and revisit those results. (You can track B.A. Breakthrough updates here.)

The baseline comparison number is slightly different but still dismal — just 11 percent of low-income students will graduate from college within six years — while for the big, nonprofit charter networks that serve high-poverty, minority students, most of them in major cities, the rates range from somewhat better to four times better and, in some cases, even higher.

The improved chances of earning a degree held while the ranks of charter alumni grew and the data became more robust. In some cases, the numbers are getting stronger and at least one prominent network, Uncommon Schools, predicts its graduates will close the college completion gap with affluent students in the next several years and surpass it a few years after that.

“Our mission is to get students to graduate from college, and that has influenced everything we do while we have students in elementary, middle and high school,” said Uncommon CEO Brett Peiser. “We’ve learned a lot about what works in helping students succeed in college, and everyone is focused on that goal.”

Ever since the first charter school was launched in Minnesota 27 years ago, educators watching the experiment have asked the same question: What lessons do they offer traditional school districts? Now, we may have that answer: Greatly improved odds that their alumni will earn college degrees.

Assuming that the charter completion rates persist, there’s a reasonable chance that their lessons learned could transform the way traditional school districts see their obligations to their graduates: How do they fare in college, and what effective methods from the charters could they start adopting to improve their outcomes later in life? Currently, almost no traditional districts track their alumni through college, although those in New York, Miami and Newark are moving in that direction.

All these issues get laid out in The B.A. Breakthrough. The book’s theme: The college success strategies pioneered by these charter networks are combining with entrepreneurial programs to spread data-driven college advising to high school students who lack it and with a growing commitment from colleges and universities to embrace low-income, first-generation students and ensure they walk away with degrees despite their vulnerabilities. Together these efforts add up to a breakthrough.

The charter network leg of the breakthrough

Given that college success is measured at the six-year mark, only recently has it become possible to evaluate the charter networks. In 2017, The 74 published a first-ever look at those rates as part of its series, The Alumni.

As with that project, the 11 percent college success rate used for comparison comes from The Pell Institute. That statistic provides an imprecise measurement, however, because it doesn’t take into account that most of these charter students are not just low-income, but also minority students living in urban neighborhoods whose college completion odds are even more daunting.

Comparing college graduation rates across charter networks is not easily done. KIPP, for example, tracks all alumni who completed eighth grade with KIPP, regardless of whether they go on to a KIPP high school. That puts KIPP in a category by itself. The other networks use the traditional approach of tracking only their high school graduates.

Even among the charter networks that track their high schoolers from graduation day, there are significant variations. While all the networks draw on the same foundational source, the National Student Clearinghouse, which matches the IDs of high school graduates to enrolled college students, some networks invest in their own tracking system, which picks up students missed by the Clearinghouse system. That makes their data more accurate and likely to produce higher rates.

Given the complexities, I divide the charter data into three groups:

Category 1 — Tracking from eighth grade, record-keeping that KIPP says is necessary to account for dropouts:

KIPP (national): As of the fall of 2017, KIPP had 3,200 alumni who were six years out of high school. The network’s national college completion rate is 36 percent for all alumni who completed eighth grade at a KIPP school and 45 percent for those who graduated from a KIPP high school. That counts students who entered a KIPP high school in ninth grade and stayed a year or more. In the national group, another 5 percent earned two-year degrees; in the group that graduated from a KIPP high school, another 6 percent earned two-year degrees.

Category 2 — Networks that use both Clearinghouse and internal tracking data:

Uplift Education (North Texas): Thirty-seven percent of the 1,075 graduates of the classes of 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 earned bachelor’s degrees within six years. When associate’s degrees are included, that climbs to 40 percent. If calculated just on the classes of 2011 and 2012, the rate would be 57 percent.

Uncommon Schools (New Jersey and New York): Fifty-four percent of their alumni earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. Among those, 39 percent earn a bachelor’s within four years. Drawing on data that track students currently enrolled, Uncommon predicts that it will close the college graduation gap with high-income students (58 percent) in the next few years. Within six years, Uncommon expects to hit a success rate of 70 percent.

DSST Public Schools (Denver): Among the 1,075 alumni, starting with the class of 2011, half earned bachelor’s degrees within six years.

YES Prep (Houston): The network has 974 alumni from the graduating classes of 2001-2012. Among the earliest graduating classes (2001-2008), 52 percent earned a two- or four-year degree within six years of high school graduation. Of the most recent graduating classes (2009-2012), 40 percent earned a four-year degree and 6 percent earned a two-year degree within six years of high school graduation.

Noble Network of Charter Schools (Chicago): Noble has 2,259 alumni who are six years or more out of high school. Among that group, 35 percent have bachelor’s degrees, 7 percent have associate’s degrees and 9 percent are still in college.

Category 3 — Charter networks that rely solely on National Student Clearinghouse data:

Achievement First (New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island): There were 74 alumni from the classes of 2010-12. Of those, 34 percent earned bachelor’s degrees within six years. Another 2 percent earned associate’s degrees.

Green Dot Public Schools (California): Green Dot has 6,601 alumni from the classes of 2004-2012. Of those, 14 percent earned bachelor’s degrees by the six-year mark. Another 15 percent completed two-year degrees. (Green Dot has a less aggressive college success program than other networks, and, as seen in its absorption of the failing Locke High School in Watts, it takes on significant challenges.)

Aspire Public Schools (California and Tennessee): Aspire has 619 alumni from the classes of 2007-2012 who have reached the six-year point. Of those, 26 percent earned bachelor’s degrees, a rate that rises to 36 percent when associate’s degrees and certificates are included.

Alliance College-Ready Public Schools (California): At Alliance, 610 of their 2,617 alumni have reached the six-year point. Of those, 23 percent have earned four-year degrees. When two-year degrees are added in, the percentage rises to 27.

IDEA Public Schools (Texas, Louisiana): At IDEA, 508 alumni have reached the six-year mark. Of those, 38 percent earned bachelor’s degrees. Another 4 percent earned associate’s degrees in that time. (Another 2 percent earned either a bachelor’s degree or an associate’s, but it’s unclear which, due to reporting issues.) The network says it is experiencing steady improvements: Whereas only 31 percent of 2009 IDEA graduates completed college in six years, 50 percent of its 2012 graduates did.

Single charter schools:

There are a few solo charters, not part of networks, with significant numbers of alumni who have passed the six-year mark.

One example from Boston, a city which has some of the longest-running charters, is Boston Collegiate Charter School. There, 51 percent of the 177 alumni six years out earned bachelor’s degrees; another 8 percent earned two-year degrees. The school appears to be experiencing sharp increases in success rates: For the class of 2014, 79 percent graduated from college within four years.

More on the data

Consider this an early take on the promise charters made to offer better odds on college success. For many of the networks, the number of alumni who have reached the six-year mark is modest. We’ll know more as larger classes graduate and reach that milestone.

Comparing the networks is difficult because some use internal tracking systems that pick up students missed by the Clearinghouse. For example, networks using only Clearinghouse data miss students exercising their privacy rights, known as “FERPA blocks” for the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. That shields their college transcripts from outside review. In a time when immigration issues are contentious and parents (and some students) could face deportation, FERPA blocks are an attractive option for families. The number of blocks varies greatly by region, with few on the East Coast exercising the option and as high as 6 percent of all students attending West Coast colleges opting to shield their records, according to the Clearinghouse.

Translation: Charter networks such as IDEA Public Schools, with many of its schools located in Texas border towns, that also rely only the Clearinghouse data, are likely to show lower success rates.

Also tricky: When comparing the charter alumni to the broader student population, what’s the right comparison number to choose? The 11 percent Pell number I’m using should be viewed as a rough marker. First, that makes the denominator all low-income students — not just low-income high school graduates — which suggests the 11 percent figure is low. But the fact that most of these networks enroll minority students from urban neighborhoods suggests 11 percent is high because the Pell number would include low-income Asian and white students, who across income levels have higher college graduation rates than black and Hispanic students. Bottom line: The 11 percent emerges as a useful if imprecise comparison figure.

Watching a network do the math

By necessity, all the college graduation data are self-reported. Outcome figures from the National Student Clearinghouse, which is private, are proprietary to the networks, which pay the Clearinghouse for the information. For the sake of transparency, I asked one network, Uncommon Schools, to open up its books for me so I could observe both processes, the Clearinghouse data combined with its own tracking data.

In April 2018, I met Ken Herrera, Uncommon’s senior director of data analytics, in Newark at North Star Academy Charter School. There, Herrera clicked on his laptop and showed me a listing of alumni. For privacy reasons, the students had been “de-identified” and showed up only as numbers on the modified Salesforce (the customized business software Uncommon and other networks use to track their alumni) program. Twice a year, said Herrera, usually in March and October, Uncommon sends a list of alumni names and their dates of birth to the Clearinghouse for tracking. Why just some? Because Uncommon saves money by omitting names of alumni who, for example, already had their college graduation confirmed through a university. In about two weeks, the Clearinghouse sends back an Excel sheet with the information it collected on the asked-about students: where they are in school and what term — fall semester, for example — they are in.

If Herrera sees a “no match,” which happens about 10 percent of the time, he and the counselors investigate. At networks that don’t track alumni individually, that student would be counted as a dropout. When digging into it further, Uncommon finds out whether they truly have dropped out by contacting the university or the family or the student, whatever means is available. They also track down whether it’s just a matter of having entered the wrong birth date or a name mix-up, such as a nickname used when enrolling in college. If it is just a bookkeeping issue, the counselors request a copy of the college transcript so the error can get fixed.

Another reason for the “no match” might be the FERPA block, which prompts the Uncommon team to contact the students and convince them to unblock their records. Some universities make records disclosure an opt-in process, done every semester, which makes life especially difficult for Herrera, because if the student fails to take action the default status is a FERPA block.

In early April each year, Herrera meets with the counseling team to sort out data omissions, a painstaking, student-by-student process. “We’ll say, ‘This is what the Clearinghouse says about the student, here’s what Salesforce says about the student. What are we going to do about this conflict?’” That leads to a counselor personally investigating: Where is the student? When all the data issues get settled, Uncommon can calculate its college success figure.

Now the trickier issue: Unlike most other networks, Uncommon predicts where its college success rate is headed. Here’s what Uncommon predicts, as noted above: In roughly six years, the college success rate will rise to about 70 percent. Given that 70 percent exceeds the rate for well-off white students, that’s a remarkable prediction. What’s it based on? Uncommon tracks its alumni by cohorts, so it can establish a historical rate for, let’s say, how many students drop out between their freshman and sophomore year in college.

“When we look at each of those [dropout points] we can predict where an individual cohort is going, based on those historical rates, and predict what we think their graduation rate is going to be,” Herrera said.

Currently, Uncommon is seeing significant improvements, such as half the historical rate of dropouts between the sophomore and junior years. Also an issue: Uncommon is growing. By the year 2022, it projects 1,000 graduates a year, compared with the roughly 400 current graduates. That also figures into the math, because younger cohorts, which are showing better persistence rates, have a bigger impact on the overall college success math. The newer cohort, for example, is showing a 50 percent success rate at the four-year mark (older cohorts achieved that only at the six-year mark). Thus the prediction: 70 percent overall success rate within six years.

So why the improved persistence? Most of that, says Herrera, comes from strengthening the high school curriculum and programs such as Target 3.0, a mandatory class to boost the grade point averages for all students with a GPA less than 2.5.

“What we found, perhaps unsurprisingly to many people, but I think really profoundly for us, was that students with higher GPAs were more likely to graduate from college,” he said. “When we cut the data, getting above a 3.0 GPA [in high school] was very significantly correlated with future college success.”

Where all this leads

Yes, it is early to be judging college success among these networks, but not premature. There are thousands of alumni in these calculations, and their academic outcomes are crucial. If their success persists and, more importantly, if their lessons learned are picked up by the far larger traditional school districts, we could be looking at one of the most successful anti-poverty programs ever seen in this country.

There’s no guarantee it will happen, but the seeds are there, all explained in the upcoming The B.A. Breakthrough.

[Read more at The 74] Read MoreAre Teacher Shortages Worse Than We Thought?

The teacher shortage is “worse than we thought,” researchers conclude in a new analysis of federal data.

The study, published by the union-backed think tank Economic Policy Institute, argues that when indicators of teacher quality are considered—like experience, certification, and training—the teacher shortage is even more acute than previously estimated. This hits high-poverty schools the hardest, the study’s authors say.

However, other researchers have pushed back against the idea of a national teacher shortage, arguing that shortages are localized and concentrated in certain subjects, like special education and high school math and science. A 2013 analysis by Education Week found that colleges are overproducing elementary teachers.

“We don’t have a national teacher labor market, we have 50 different labor markets,” said Daniel Goldhaber, the director of the Center for Education Data and Research at the University of Washington.

And in most states, the teaching force has actually grown faster than student enrollment.

Still, Elaine Weiss, a co-author of the EPI report and the former national coordinator for the Broader Bolder Approach to Education campaign, noted that schools across the country have reported difficulties hiring teachers. An Education Week analysis of federal data found that all 50 states reported experiencing statewide shortages in at least one teaching area for either the 2016-17 or 2017-18 school year.

“If schools are reporting that they need teachers, and that they are struggling to find teachers to fill those spots, … I find it very hard to understand how there can’t be a teacher shortage,” Weiss said.

A few years ago, the Learning Policy Institute, a K-12 think tank led by Linda Darling-Hammond, who is now the chairwoman of California’s board of education, released a package of reports that projected an annual national shortfall of 112,000 teachers by 2018. The need for more educators would continue to grow well into the 2020s, the group predicted.

These estimates likely underestimate the magnitude of the problem, the EPI report says, because they consider how many new qualified teachers are needed to meet new demand. But not all current teachers are highly qualified—a term that, according to the report, means they’re fully certified, they were prepared through a traditional-certification program, they have more than five years experience, and they have relevant experience in the subject they teach.

Goldhaber pushed back against the LPI study, saying the methodology used was flawed and the projections have not materialized: There aren’t currently more than 100,000 people missing from the teaching force, he said.

Still, certain subjects (like special education, high school science and math, foreign language, and bilingual education) and locations (like high-poverty and rural areas) perennially lack teachers. The EPI report doesn’t delve into shortages in subject areas, but it does focus on the growing lack of highly qualified teachers in high-poverty schools.

Who and Where Are ‘Highly Qualified’ Teachers?

“Highly qualified” was, for many years, an important technical term with the force of law behind it. The prior federal law, the No Child Left Behind Act, defined highly qualified teachers as those who held a bachelor’s degree, state certification, and have demonstrated content knowledge. The law required that states staff each core academic class with those teachers. But NCLB’s replacement, the Every Student Succeeds Act, threw out that requirement.

Instead, ESSA says that teachers in schools receiving Title I funds just need to fulfill their state’s licensing requirements. States are also required to define “ineffective,” “out-of-field,” and “inexperienced” teachers, and make sure that poor and minority students aren’t being taught by a disproportionate number of them.

The EPI report expands the NCLB definition of highly qualified teachers to include experience and preparation. The number of teachers who meet EPI’s criteria of highly qualified has declined over time, according to the group’s analysis of federal data.

Alternative-certification programs bring in more teachers of color, male teachers, and teachers who attended selective colleges than traditional prep programs do, past reports have found. But research has also found that alternatively certified teachers quit at higher rates and report feeling less prepared than their traditionally certified colleagues.

The shortage of teachers who meet all these criteria is most pronounced in high-poverty schools, the EPI report finds. For example, 80 percent of teachers in low-poverty schools have more than five years of experience, compared to 75 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools. And about 73 percent of teachers who work in low-poverty schools have an educational background in the subject they teach, compared to 66 percent of teachers in high-poverty schools.

It’s worth noting that high-poverty schools struggle with hiring and retaining teachers in general—not just teachers who meet EPI’s criteria of highly qualified.

But the study’s authors write that highly qualified teachers are in high demand, and are more likely to be recruited by affluent school districts that might be able to offer better working conditions. Low-income children are consistently more likely to be taught by teachers who are not fully certified or who have less experience, the report says.

Indeed, a federal 2016 report found that uncertified teachers were more prevalent among high-poverty schools and schools with high percentages of students of color and English-language learners.

The EPI authors are planning to release five more papers analyzing the conditions that contribute to the shortage of who they deem highly qualified teachers, particularly in high-poverty schools. The papers will look at challenges related to teacher recruitment, pay, working conditions, and professional development, as well as give recommendations to policymakers.

(The National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers are some of EPI’s top donors. The think tank gets about 30 percent of its funding from unions, and the rest from foundations, individuals, and other organizations.)

These papers are coming at a time when teachers across the country have been protesting against low wages and crumbling classrooms, Weiss noted.

[Read more at Education Week] Read MoreMemphis parent advocacy group spreading model to other cities, most recently Nashville

Sonya Thomas met a handful of fellow Nashville parents last summer, and quickly realized they all had something in common – a deep dissatisfaction with the schools their kids were attending.

Thomas said they wanted to do something big and drastic, something more than just talking about it. But they didn’t know what that was until they met Sarah Carpenter, a vocal Memphis parent and leader of advocacy group Memphis Lift, at a Nashville parent summit.

“The thing that most stood out to me, is how much they help their other parents,” said Golding Chalix, one of the leaders of the new parent advocacy group Nashville Propel. “To me, that was really inspiring to see parents fighting and working toward goals in a more organized way, especially being a Latina mom wanting to fight this fight.”

Nashville is the latest city to copy pieces of the Memphis Lift model. Carpenter said she’s been meeting with parents in Oakland and Atlanta to help get their programs started. An Indianapolis nonprofit launched an advocacy fellowship earlier this year to give low-income families and families of color more voice in their local schools – and pointed to Memphis Lift as one of the model examples of parent engagement work.

The handful of parents that make up the backbone of Nashville Propel started meeting last fall, and held a joint press conference with Memphis Lift last week at Capitol Hill to talk about their priorities, which hinge on educating parents of students in Nashville’s lowest-performing schools.

Memphis Lift has had success in reaching parents door-to-door and building a grassroots support system through its own advocacy fellowship. The group has held dozen of events at its North Memphis headquarters, at schools, and has shown up in force to school board meetings as its sought to rally parents.

Carpenter, who helped start Memphis Lift in 2015, said the national interest started three years ago when she spoke at a Teach for America event.

“Our phones have been ringing off the hook since,” Carpenter said. “It’s awesome to connect with other parents like this who have the same problems. They’re regular parents just like us trying to make a change in their city for low-performing schools.”

Thomas said the Nashville group is copying Memphis Lift’s strategies in door-to-door outreach and from its Public Advocate Fellowship, which was created three years ago by Natasha Kamrani and John Little, who came to Memphis from Nashville to train local parents to become advocates for school equity.

When Memphis Lift launched, it was viewed warily by some local school leaders who doubted the group’s independence because of its close relationship with Kamrani, former director of Tennessee’s branch of Democrats For Education Reform and wife of Chris Barbic, founding superintendent of the Achievement School District. Little ran Strategy Redefined, a Nashville-based education consultant firm that helped launch Memphis Lift.

The Memphis fellowship has trained 327 members, mostly women, since it launchedin 2015 on how to navigate an increasingly complex school choice system and how to understand state data on schools. This past year, Memphis Lift offered training for Spanish-speaking parents and is working to create its first all-male cohort for fathers and grandfathers.

Nashville Propel just finished its first parent fellowship, which was completed by 29 English and Spanish speakers. Thomas said a big goal for Propel is to help parents understand what it means that their children attend priority schools, the state’s designation for Tennessee’s lowest-performing schools.

PHOTO: Nashville PropelOn March 9, members of the Nashville Propel joined together to officially launch their group.

“We’re finding parents don’t clearly understand what this means,” Thomas said. “Some even think priority school means their school is doing well. Once we explain it to them, they realize the gravity of it.”

With neighborhood events over the last few months, Nashville Propel has spoken with about 700 priority-school parents. Within a year, the group wants reach 4,000, which is 75 percent of Nashville parents whose kids go to low-performing schools, Thomas said.

Tremayne Haymer of Nashville Propel said they are going to advocate for Metro Nashville Public Schools to release a public plan for the city’s 21 priority schools. Six Nashville schools were on the list in 2012.

“From 2011 to now, every time the list comes out the number gets greater,” Haymer said. “We’re going to be in the same boat Memphis was in a few years ago. Our plan is a year from now to get clear-cut resources from the district on how to combat this problem.”

Unlike Memphis Lift, Nashville Propel does not yet have a full time staff, but Haymer said they are actively looking for funders. Haymer added that Propel has gotten some startup funding from the Scarlett Family Foundation, which focuses its education philanthropy on Middle Tennessee.

Memphis Lift has received $1.5 million from the Walton foundation since 2015, and its fellowships are funded in part by the Memphis Education Fund. (Chalkbeat also receives support from local philanthropies connected to Memphis Education Fund and The Walton Family Foundation. You can learn more about our funding here.)

Despite initial leeriness toward Memphis Lift’s funders, the group has criticized and supported both district and state-run schools over the years, such as marching against the closure of an Achievement School District charter school and lobbying county commissioners last year for more funding for Memphis’ traditional school district.

“If it’s a charter school not working, close it down,” Carpenter said. “If it’s a district school not working, do the same. We want it shut down, period. We know what our children deserve in an education.”

Thomas echoed the sentiment.

“We’re not pro-traditional schools, private schools or charter schools,” Thomas said. “We have no other agenda except empowered parents whose children are taken care of.”

[Read more at Chalkbeat] Read More